The educational content in this post, elaborated in collaboration with Lesaffre, was independently developed and approved by the GMFH publishing team and editorial board.

How our brain and our gut talk to each other

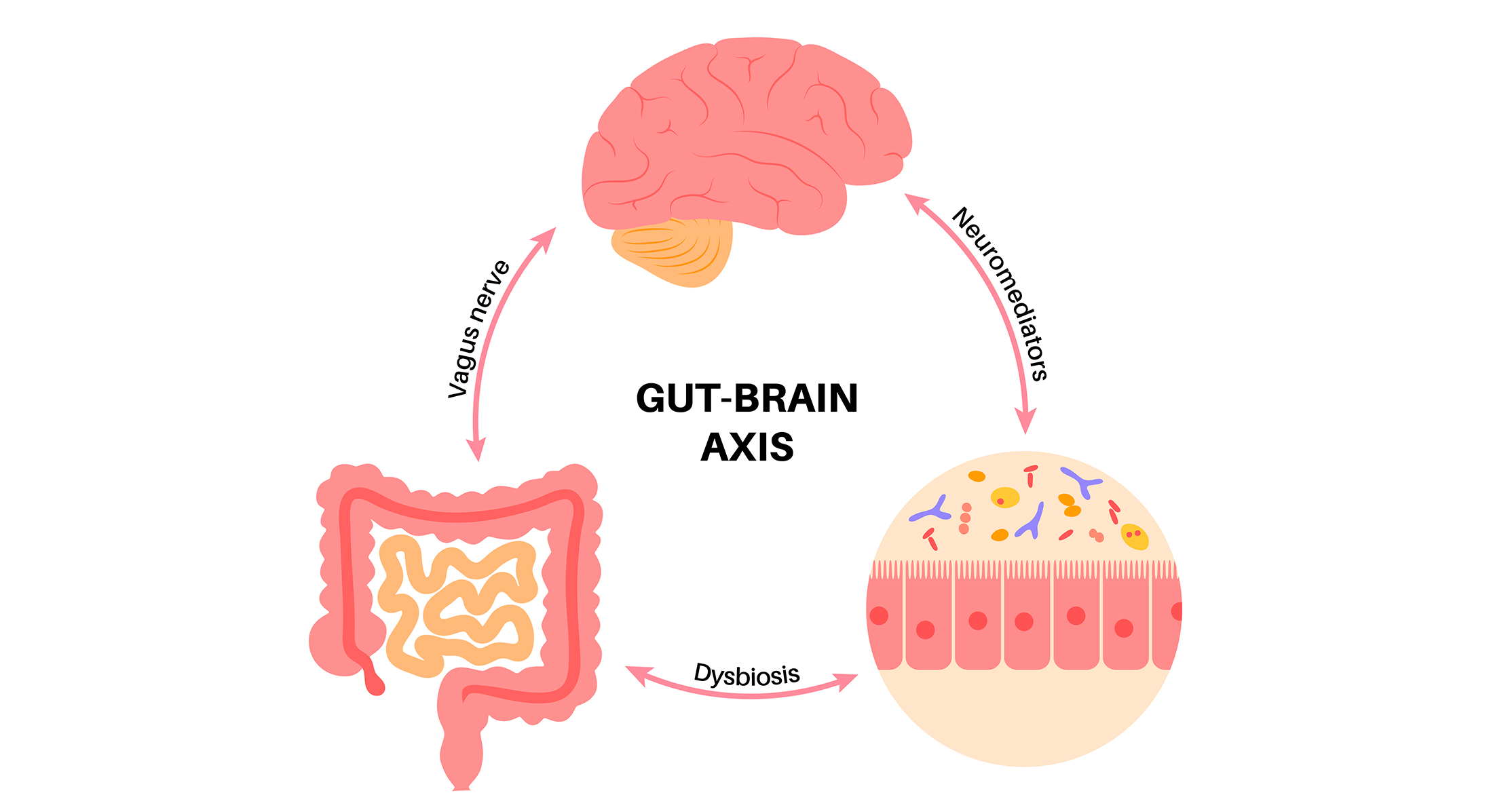

The brain and gut are in constant communication with each other, which allows important body functions such as digestion and appetite to happen. The concept of the gut-brain axis dates back to the 19th and 20th centuries, with observations by Darwin, Beaumont and Cannon that the emotional state can affect the gut.

With the recent understanding of the importance of the microbiota in health, the axis has expanded to microbiota-gut-brain axis. The butterflies you feel in your tummies when you fall in love and those unwelcome cramps before an exam are two examples of the connection between the gut and the brain.

Intestinal movements alteration, an increase in pain sensation in internal organs, altered immune function, disturbed gut microbiota and altered functioning of central nervous system are central in the origin of disorders of gut-brain interaction such as IBS, previously classified as a functional gastrointestinal disorder.

While how gut microbes influence the brain – and vice versa – is still being unpicked, scientists have learned three major routes through which the gut microbiota affects the gut-brain axis:

- Direct neural signaling: the vagus nerve and the spinal nerves supplying colon are the main link between your enteric nervous system and your brain, allowing a direct communication between your gut and your brain like your mobile phone.

- Hormones circulating in the blood, neurotransmitters and neuroactive mediators produced by gut microbiota: this endocrine pathway acts like a post office mail that involves intermediate actors before finally reaching to the brain.

- Immune cells: cytokine secretion by immune cells have effects both locally in the gut and on brain function, acting like a fire alarm that activates when something is wrong.

Disturbances in any of these ways can result in mental disorders.

During the last decade or two, we have learned that gut microbes can communicate with the brain and affect its functions. Although most of the original studies were performed in animal models, accumulating evidence now shows that this microbiota-brain communication occurs also in human studies. We know that the gut bacteria can produce many neurotransmitters, signaling molecules that are used in our neural system, they can modify production of human hormones, for example those involved in stress responses, or shape our immune system, interacting with multiple immune cells in our gut. The communication between the gut microbes and our brain is bi-directional, that means our neural system can also affect composition and activity of gut microbiota.

In healthy individuals, there is a balanced microbiota that lives in symbiosis with its host. If this healthy co-habitation is perturbed by stressors, changes in environment, diet, infections or antibiotics, it can have negative effects on the host’s immune and neural systems. Multiple trials have shown that many patients with psychiatric disorders have different microbiota composition than healthy controls. This may be a consequence of the psychiatric disease, but several studies demonstrated that transferring microbiota from patients with either anxiety or depression can induce abnormal behavior in germ-free mice. And this suggests, that at least in some patients, the abnormal microbiota has a causal role in mental health disorders.

Anxiety and depression are common in patients with IBS

With the advent of brain imaging, scientists have figured out the reciprocal nature of the relationship between our gut and brain. Gut responses towards specific foods can activate key brain areas involved in anxiety and stress and explain that patients with IBS have a poor food-related quality of life.

Patients with IBS change eating habits based on beliefs on how they think food impacts symptoms. But food avoidance and restriction in IBS is associated with more severe gastrointestinal, psychological and physical symptoms, reduced quality of life and reduced intake of nutrients.

The summary of most relevant studies have shown that patients with IBS –especially women compared to men– are commonly affected by anxiety (4 in out 10 patients) and depression (3 in out 10 patients). The opposite is also true, meaning that patients with anxiety and depression have a two-fold risk of developing IBS.

The link between psychological symptoms and IBS is important because the higher the number of psychological alterations, the higher the severity of IBS is. In addition, the number of prior psychological events is a relevant risk factor for the later IBS onset. But it is not only that IBS is associated with anxiety and depression, but also that the severity of depression in patients with IBS is higher than in healthy individuals.

When it comes to who the chicken and the egg, it seems that gut is the main origin of digestive and extraintestinal symptoms in many patients rather than the brain. The gut symptoms of IBS precede mood disorder in two-third of cases, whereas a third of patients develop mood disorders before the onset of gut symptoms.

A large proportion of patients with IBS suffer from anxiety and depression, which may in some patients precede the onset of IBS, in some it may be a consequence of dealing with chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel habits, and in other patients these abnormalities have a common origin. Both IBS and psychiatric disorders, including anxiety and depression, have been linked to low grade inflammation.

Many patients with chronic inflammatory disorders, such as Inflammatory Bowel Disease or rheumatoid arthritis, suffer from anxiety and depression, and their severity increases in parallel with the severity of their bowel or joint inflammation, clearly linking the immune system to psychiatric disorders.

Independently of their origin, mental health issues should be diagnosed and treated in patients with IBS. Unfortunately, gastroenterologists are not, in general, well trained in assessing mental health, and this is something we should improve in near future because addressing psychiatric comorbidities should be an integral part of management of patients with IBS.

Which is the origin of psychological symptoms in IBS?

There is no unique cause that explains why anxiety and depression are common in patients with IBS. Every factor that is able to change the microbiota-gut-brain axis is susceptible to influence the development of psychological symptoms. Below you can find the most relevant factors studied until now:

- Genes: IBS shares up to 70 unique genes with psychiatric disorders. These genes are enriched for functions related to immune and nervous systems that are upregulated in the brain and downregulated in gastrointestinal organs.

- Disturbances in the gut and brain maturation during early life: infant brain and gut microbiota develop in parallel. Antibiotics, malnutrition, chemicals, stress and abuse can alter the normal development of brain and gut microbiota and affect the risk of developing IBS later in life.

- An altered intestinal microbiota: the link between gut disorders, in particular abdominal pain, diarrhea and constipation, and mental health dates back from the late 19th The “autointoxication theory”, defined as alterations to intestinal microbiota and permeability, was suggested in 1914 as a contributor for some of the overlap between emotional disorders and digestive problems.

These early observations made by dermatologists, surgeons and microbiologists have recently been confirmed by studies showing that the gut microbiota composition and/or function is altered in social anxiety disorder, depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

- Gut immune system activation: up to 70% of our immune system is in our gut and an activation of gut immune cells, particularly mast cells, can lead to abdominal pain.

- Activation of specialized gut cells: an increased activity of gut enterochromaffin cells in mice, which are involved in producing most of the body’s serotonin, show a striking sex difference in gut pain, perhaps explaining why IBS is more common in females than in males.

- Changes in diet: during the last 20 years the food industry have been started using in a massive way glutamate as an ingredient of most food staples. Glutamate is used as a neurotransmitter between enteroendocrine cells and neurons and prolonged activation of glutamate receptors can trigger neuroinflammation. As a result, recent small studies have started exploring decreasing glutamate in diet as means to reduce anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorders.

IBS is associated with low-grade gut inflammation, which may be a consequence of previous gut infection, or results from abnormal immune system responses to dietary antigens or gut bacteria. In some cases, the gut microbes secrete molecules that stimulate the immune system, which gets activated and start producing additional pro-inflammatory mediators, as it is the case with bacterial histamine.

As mentioned earlier, these inflammatory mediators may trigger anxiety and depression. This has been documented in murine translational studies, which showed that low-grade gut inflammation induced by transplantation of microbiota from patients with IBS into mice can induce anxiety-like behavior. We also know that altering gut microbiota composition with antibiotics can induce changes in behavior, not only in mice but also in some patients, and that treatment with specific probiotic bacteria can improve patients’ mood. Unfortunately, the detailed underlying mechanisms of these detrimental or beneficial effects are still not well understood.

Based on the link between gut microbiota and mental health, some clinical trials have started exploring how changing our microbiome through diet, fecal transplants, antibiotics, prebiotics and probiotics could have benefits for gastrointestinal and mental disorders. In this regard, the term “psychobiotic” was coined in 2013 to describe any exogenous intervention that impacts mental health through the gut microbiome.

Many studies targeted gut microbiota through diet, prebiotics, probiotics or even fecal microbiota transplantation, some of them with promising results. During the last several years there were several studies investigating effect of fecal microbiota transplantation, meaning delivering stool microbiota from healthy individuals into patients with IBS. When putting their results together, we see some beneficial effects on IBS symptoms, mainly when the healthy microbiota was delivered into the small intestine.

Similarly, several probiotics appear to provide symptomatic benefit in patients with IBS, whether it is pain, abnormal bowel habits or bloating. These probiotics include several bacterial strains of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Escherichia and Bacillus, and yeast Saccharomyces. Probiotics appear to also improve symptoms of depression but there is less evidence for their benefit to ameliorate anxiety. Premysl Bercik’s research group has performed a pilot study to investigate effects of Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 on depressive symptoms in patients with IBS, and also studied how this probiotic affects patients’ brain activity by functional magnetic resonance imaging. We found that after 6 weeks of the probiotic treatment, the patients reported improved mood and IBS symptoms, which was associated with changes in neural activity in several brain areas that regulate mood, and which are usually targeted by classical antidepressive mediations.

Altogether, there is growing evidence to suggest that microbiota plays an important role in IBS, as well as mental health disorders. Although we still do not fully understand the precise mechanisms of the communication between the gut bacteria and the brain, we have started to take advantage of its treatment potential. In the next decade, we will have more microbiota-based diagnostic and therapeutical tools which will help us in management of patients with IBS and their psychiatric comorbidities.

Take-home messages

- While the concept of gut-brain axis is not new, scientists are understanding better how our gut and our brain talk to each other in order to develop novel treatments for managing psychologic conditions in patients with IBS.

- IBS is associated with anxiety and depression and emerging data show that the origin of psychological problems in patients with IBS may rely mostly in the gut rather than in the brain.

- Changing our microbiome through diet, fecal transplants, antibiotics, prebiotics and probiotics emerge as a new tool for managing gastrointestinal and mental disorders.

References:

De Palma G, Collins SM, Bercik P. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut Microbes. 2014; 5(3):419-29. doi: 10.4161/gmic.29417.

Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features, and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(6):1262-79. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032.

Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012; 13(10):701-12. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346.

Guadagnoli L, Mutlu EA, Doerfler B, et al. Food-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2019; 28(8):2195-2205. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02170-4.

Melchior C, Algera J, Colomier E, et al. Food avoidance and restriction in irritable bowel syndrome: relevance for symptoms, quality of life and nutrient intake. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022; 20(6):1290-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.004.

Zamani M, Alizadeh-Tabari S, Zamani V. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019; 50(2):132-43. doi: 10.1111/apt.15325.

Midenfjord I, Borg A, Törnblom H, et al. Cumulative effect of psychological alterations on gastrointestinal symptom severity in irritable bowel syndrome. 2021; 116(4):769-79. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001038.

Creed F. Risk factors for self-reported irritable bowel syndrome with prior psychiatric disorder: the lifelines cohort study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022; 28(3):442-53. doi: 10.5056/jnm21041.

Zhang QE, Wang F, Qin G, et al. Depressive symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Int J Biol Sci. 2018; 14(11):1504-12. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.25001.

Koloski NA, Jones M, Talley NJ. Evidence that independent gut-to-brain and brain-to-gut pathways operate in the irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia: a 1-year population-based prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016; 44(6):592-600. doi: 10.1111/apt.13738.

Tesfaye M, Jaholkowski P, Hindley GFL, et al. Shared genetic architecture between irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric disorders reveals molecular pathways of the gut-brain axis. Genome Med. 2023; 15(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s13073-023-01212-4.

Bested AC, Logan AC, Selhub EM. Intestinal microbiota, probiotics and mental health: from Metchnikoff to modern advances: Part I – autointoxication revisited. Gut Pathog. 2013; 5(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-5-5.

Butler MI, Bastiaanssen TFS, Long-Smith C, et al. The gut microbiome in social anxiety disorder: evidence of altered composition and function. Transl Psychiatry. 2023; 13(1):95. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02325-5.

Zhu F, Tu H, Chen T. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in depression: the potential pathophysiological mechanisms and microbiota combined antidepression effect. Nutrients. 2022; 14(10):2081. doi: 10.3390/nu14102081.

McGuinness AJ, Davis JA, Dawson SL, et al. A systematic review of gut microbiota composition in observational studies of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2022; 27(4):1920-35. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01456-3.

Zhou GQ, Huang MJ, Yu X, et al. Early life adverse exposures in irritable bowel syndrome: new insights and opportunities. Front Pediatr. 2023; 11:1241801. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1241801.

Bayrer JR, Castro J, Venkataraman A, et al. Gut enterochromaffin cells drive visceral pain and anxiety. Nature. 2023; 616(7955):137-42. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05829-8.

Brandley ET, Kirkland AE, Baron M, et al. The effect of the low glutamate diet on the reduction of psychiatric symptoms in veterans with Gulf War Illness: a pilot randomized-controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 13:926688. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.926688.

Sasso JM, Ammar RM, Tenchov R, et al. Gut microbiome-brain alliance: a landscape view into mental and gastrointestinal health and disorders. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2023; 14(10):1717-63. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00127.

Pinto-Sanchez MI, Hall GB, Ghajar K, et al. Probiotic Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 reduces depression scores and alters brain activity: a pilot study in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2017; 153(2):448-459.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.003.

Mourey F, Decherf A, Jeanne JF, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae I-3856 in irritable bowel syndrome with predominant constipation. World J Gastroenterol. 2022; 28(22):2509-2522. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i22.2509.

Pinto-Sanchez MI, Hall GB, Ghajar K, et al. Probiotic Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 reduces depression scores and alters brain activity: a pilot study in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2017; 153(2):448-459.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.003.